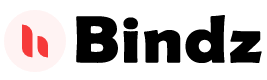

Man United are edging forward with their plans to build a 100,000-seater stadium that when finished will likely be among the best and most lucrative. But at £2-3bn, who is going to pay for it?

We can probably rule out one name from the get-go. The Glazer family, who sold Sir Jim Ratcliffe nearly 28 per cent of the club almost exactly one year ago, have never been interested in United’s infrastructure.

The Glazers have reaped almost £450m in dividends since they took over the club via a leverage buyout in 2005, which incidentally makes them the second longest serving owners in the Premier League.

| Premier League club | Year acquired (major stake) |

| Tottenham | 2001 |

| Manchester United | 2005 |

| Manchester City | 2008 |

| Brighton | 2009 |

| West Ham | 2010 |

| Liverpool | 2010 |

| Leicester | 2010 |

| Crystal Palace | 2010 |

| Arsenal | 2011 |

| Brentford | 2012 |

| Fulham | 2013 |

| Wolves | 2016 |

| Nottingham Forest | 2017 |

| Aston Villa | 2019 |

| Newcastle | 2021 |

| Ipswich | 2021 |

| Southampton | 2022 |

| Chelsea | 2022 |

| Bournemouth | 2022 |

| Everton | 2024 |

United have spent a fraction of that on infrastructure over the same period, with the Glazers only willing to eat into their dividends unless Carrington or Old Trafford are – quite literally – falling part.

Even then, it came out of the club’s purse, not their own.

One segment of both the Project Big Picture and European Super League proposals co-authored by the Glazers, copies of which have been seen by UIF, would have seen clubs pay into a central infrastructure pot.

Yes, that means they effectively wanted rival clubs to cover the costs of their own negligence.

To an extent, the owners’ chickens have come home to roost as the sorely needed upgrades to the stadium and training ground meant the market balked at their £6bn valuation of the club in 2023.

That meant Ineos and Ratcliffe were brought in as minority equity partners. And for all their faults and missteps, they have shown far more interest in giving the club what it needs to be successful again.

Unfortunately for United fans who have been asked to shoulder the burden in terms of ticket prices, it will be many years before Ratcliffe’s ambitions for Old Trafford bear fruit.

Getting sign-off from the relevant regulator bodies will be a glacial process, as will construction itself. However, arriving at a suitable funding structure could be just as complex and laborious.

Despite the pearl-clutching on social media over Chancellor Rachel Reeves’ support for the project, the UK government won’t be paying for it.

If they contribute fanatically at all, it will be for the redevelopment of the external infrastructure needed to facilitate the sprawling stadium complex – public transport links, roads etc.

A cursory Google search meanwhile will tell you that Ratcliffe’s personal fortune is around £25bn, but most of that is illiquid. In other words, he doesn’t have £2-3bn in cash down the back of his sofa.

Bonds and debentures, which have historically been used by the likes of Arsenal to fund stadium projects, are no longer a common financing model for capital expenditure projects in football.

That leaves one option: private investment. This could come in the form of commercial loans or equity investment from a new co-owner.

- READ MORE: The two details of Patrick Dorgu’s Man Utd transfer prove Ineos are fixing major Glazer errors

Sir Jim Ratcliffe and Ineos likely to take on more debt to cover stadium bill, says football finance expert

Last summer, it emerged that United had engaged the Bank of America about funding the Old Trafford redevelopment project.

Second only to JPMorgan Chase in the list of the world’s largest banks, the Bank of America is familiar to United and the Glazers specifically due to events pre-dating Ratcliffe’s part-takeover.

Sheikh Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani appointed the Bank of America as his chief advisors in his failed bid to buy United in early 2023.

Interestingly, it was reported late last year that – despite being linked to the likes of Tottenham, who are looking for fresh investment – Sheikh Jassim still only has eyes for United.

With equity investment one possible element of a funding package, the alliance between the Qatari royal and the Bank of America could – theoretically, at least – be significant.

The Bank of America was among the lenders who facilitated the construction of the Tottenham Hotspur Stadium too, most of which was funded by loans with fixed interest rates of 2-3 per cent.

| Stadium | Cost (adjusted for inflation) | Location | Opened |

| SoFi Stadium | $5.5 billion | California, USA | 2020 |

| MetLife Stadium | $1.99 billion | New Jersey, USA | 2010 |

| Allegiant Stadium | $1.90 billion | Nevada, USA | 2020 |

| Wembley Stadium | $1.85 billion | London, UK | 2007 |

| Yankee Stadium | $1.79 billion | New York, USA | 2009 |

| AT&T Stadium | $1.79 billion | Texas, USA | 2009 |

| Mercedes-Benz Stadium | $1.56 billion | Atlanta, USA | 2017 |

| Singapore National Stadium | $1.41 billion | Kallang, Singapore | 2014 |

| Tottenham Hotspur Stadium | $1.33 billion | London, England | 2019 |

| Optus Stadium | $1.17 billion | Perth, Australia | 2017 |

Speaking exclusively to UIF, Liverpool University football finance lecturer and industry insider Kieran Maguire said that it would be impossible for United to get those kinds of rates from the Bank of America in today’s market.

“I think Man United’s chances of replicating the Spurs deal are close to zero,” said

“At the same time, the United brand is held in such high esteem, the new stadium can significantly impact revenues. There is no reason why the new stadium can’t be doing £250m per year as far as sales are concerned.

“You’re increasing capacity by 25,000 but if you look at the SoFi Stadium and its commercial capabilities, that is what United will be licking their lips about.

“If they go down the multi-function, multi-sport model like Spurs, there is no reason they can’t easily cover the interest costs.

“Even if you doubled Spurs’ interest costs from the current £25m to around £50m, they have made so much more money from commercial activities that they can more than cover that.

“United are a blue-chip member of the Premier League and, yes, they aren’t having a good season, but they can ride that out.

| Position | Team | Played MP | Won W | Drawn D | Lost L | For GF | Against GA | Diff GD | Points Pts |

| 11 | 24 | 9 | 4 | 11 | 42 | 42 | 0 | 31 | |

| 12 | 24 | 7 | 9 | 8 | 28 | 30 | -2 | 30 | |

| 13 | 24 | 8 | 5 | 11 | 28 | 34 | -6 | 29 | |

| 14 | 24 | 8 | 3 | 13 | 48 | 37 | 11 | 27 | |

| 15 | 24 | 7 | 6 | 11 | 29 | 46 | -17 | 27 |

“Whether lenders would want to put in 100 per cent of the costs of a new stadium is a separate issue.

“They would probably want the owners to take on an element of risk, so it then comes down to Ratcliffe and what he is prepared to do.

“You hear a variety of stories about Ratcliffe’s wealth. His net worth is around £15bn but much of that is tied up in assets rather than cash.

“If he is genuine, however, there is no reason he can’t liquidise some of those assets to provide funding for the stadium.

“If United wanted to go for a 100 per cent mortgage rate, they would pay higher interest rates.

“So you can see why Ratcliffe could do a deal with the Bank of America or another lender to ensure the stadium is fully costed.”

- READ MORE: Sir Jim Ratcliffe’s £300m PSR ‘smokescreen’ as expert expects even more Man United ‘cutbacks’

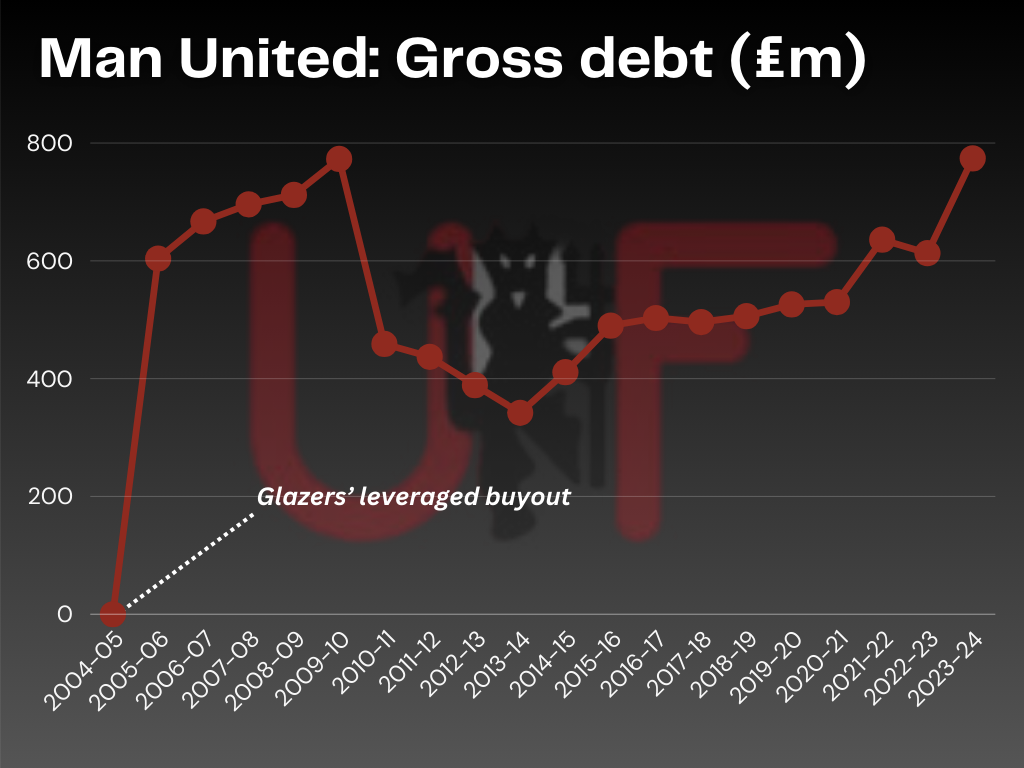

How much debt are United in ahead of Old Trafford 2.0 project?

Interest rates are stubbornly high at the moment as the world’s major economies attempt to curb inflation.

Debt isn’t a dirty word in the world of high finance – the opposite, in fact.

But with United already in colossal debt and with revenues likely to be volatile during a period of transition on the pitch under Ruben Amorim, caution is needed.

The Glazers loaded the Red Devils with around £500m worth of debt as part of the takeover two decades ago, with interest on the loans seeing the total figure peak at approximately £800m around 2010.

United’s listing on the New York Stock Exchange cut that figure in half, but it has since spiralled again and is almost at is all-time high once again.

The club will supersize its revenues overnight as soon as Old Trafford 2.0 opens its doors, but the last thing they need is for a huge debt burden to eat into that financial surge.

from United In Focus https://ift.tt/FYjKQac